What to Replicate?

By Peder M. Isager

June 9, 2018

Justifications of study choice from 85 replication studies.

In their recent BBS article, Zwaan et al. (2017) synthesized arguments for and against replication research and laid out a convincing argument for the value of direct replication in science. My collaborators and I wrote a commentary on this article (Coles et al. 2018). In it, we argued that in order to maximize the utility of replication in a science that is operating under resource constraints (there is only so much time and money for doing research), we need to deal with the question of when to replicate. In other words, assume that a researcher has limited resources and can either replicate a previous study or run an original study of their own. Both of these options have costs (e.g. money for subject recruitment, time spent conducting the study) and benefits (e.g. theoretical innovation, estimate accuracy, societal impact). Considering both options, the researcher will need to decide which has the higher cost/benefit ratio.

In a another project I am working on for the Open Science Collaboration, we are trying to develop some formalized tools to help researchers justify their decisions of which studies to replicate. We make the assumption that every researcher has to make decisions under resource constraints, and we assume that they have already decided to conduct a replication. They now face a new problem: There are many original findings that they could replicate. Which one should they choose? We may all agree with Zwaan et al. (2017) that “the idea that observations can be recreated and verified by independent sources is usually seen as a bright line of demarcation that separates science from non-science,” but that does not really help us prioritize which observations to recreate. What makes a study more valuable to replicate than another?

In the process of coming up with answers to this question, I thought it would be useful to take a look at how researchers “in the wild” justify their replication efforts. They must have some reason for choosing a specific study to replicate, and it seems reasonable to assume that authors would provide these reasons in their report. So I went to the “Curated Replications” dataset at curatescience.org and started working my way through the links in the table. Eighty-five papers later, here are my takeaways.

Replication Justifications

Based on my reading of and subjective judgement of similarity between the justifications for study selection mentioned in the 85 replication reports, I have grouped them into five major categories: theoretical impact, personal interest, academic impact, public/social impact, and methodological concerns. For each category I have included a short description, and a few illustrative quotes with a reference to the quoted articles in each case. It should be noted that any given replication will usually deploy more than one justification for why a finding was considered valuable to replicate, often drawing from several different categories. At the end of this article you can find a link to a spreadsheet containing the justification quotes I have based my review on, as well as article DOIs, for almost all of the 85 reports reviewed (some reports did not have a justification and/or DOI).

Theoretical impact

One of the most widely deployed justifications for replication is arguing for the theoretical significance of the finding. These arguments are sometimes quite specific:

Example: IJzerman et al. (2014)

“This latter effect [age*gender interaction] is an important component of the theory that sexual jealousy is evolutionarily prepared, as the theory predicts sex differences for both age groups…”

Other times justifications are more general. They might simply state that the original finding has generated a lot of novel research, or that it has been important for theorizing within the field:

Example: Cheung et al. (2016)

“This highly cited paper serves as a cornerstone for the theoretical importance of relationship commitment as a predictor of relationship outcomes, including forgiveness. The findings have important implications for the theoretical understanding of forgiveness…”

Personal interest

Similar to theoretical impact, though harder to nail down in a specific quote, personal interest represents the author’s own interest in the topic they are studying. A large portion of replications I reviewed were phrased in such a way that the authors seemed partially motivated by their own personal interest in the topic at hand. Some illustrative cases are found in conceptual replications, where the replication itself is often a stepping stone on the way to what the authors really care about: extending current research paradigms.

Example: Ronay et al. (2017)

“The goal of the current research was twofold. First, we intended to replicate Carney et al.’s (2010) main effects and to test the possibility that the relationship between embodied power and risk-taking is statistically mediated by increases in testosterone… Our second goal was to test the possibility that elevated levels of testosterone increase overconfidence, which in turn may facilitate risk-taking…”

Academic impact

Another common justification for choosing a finding to replicate is to refer to the academic impact of either the original finding or the paper it is reported in. There are many indicators of academic impact researchers can use, some more quantifiable than others, but all are related in some way to the standing of the paper among scientists in the field. Examples of less quantifiable justifications include the following:

Example (generative finding): Lynott et al. (2014)

“The [original] findings… has impacted subsequent research investigating how experiences of hot and cold can prime other behaviors…”

Example(textbook case): Vermeulen et al. (2014)

“Moreover, the study appears in nearly every student textbook on persuasion and consumer psychology (e.g., Cialdini, 2001; Fennis & Stroebe, 2010; Peck & Childers, 2008; Saad, 2007)…”

Example (“classic” study): Wesselmann et al. (2014)

“Schachter’s groundbreaking demonstration of the deviation-rejection link has captivated social psychologists for decades. The findings and paradigm were so compelling that the deviation-rejection link is often taken for granted and sometimes may be misrepresented…”

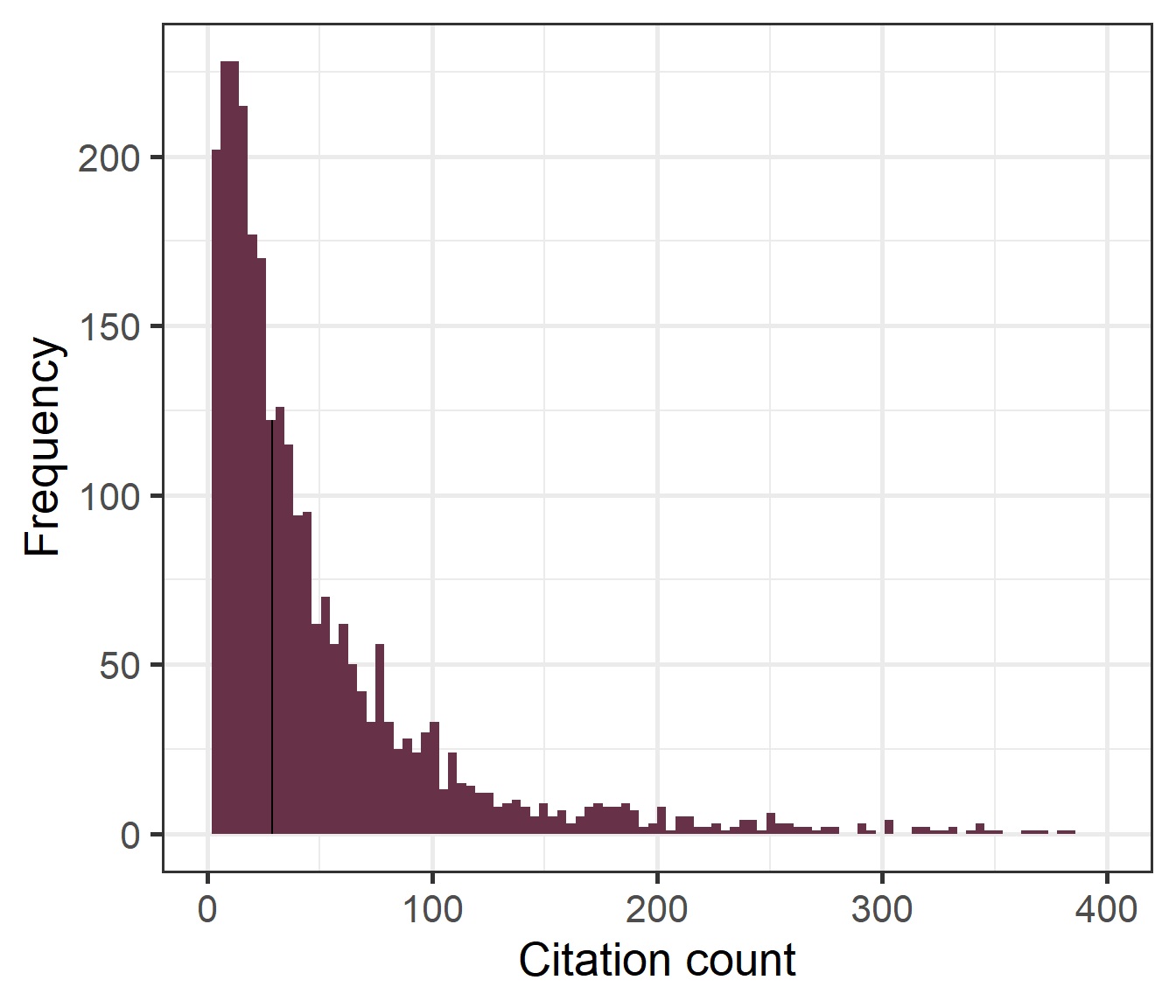

A more quantifiable approach is to quote the citation impact of the original study in question. In these cases it is often common to state the date and source of the citation number as well. Though often used, it is not apparent what constitutes a “widely cited” article. In the 85 articles reviewed here, quoted numbers range from 21 to over 1600. To provide a reference point for these numbers, I acquired the Crossref citation counts for 2854 empirical papers from the psychology literature. These papers are part of a dataset of psychological effects reported in meta-analyses, which is currently being curated by our lab. Median citation count was 29. Citation frequencies are plotted in Figure 1.

Example (citation count): Harris et al. (2013)

“Because the paper has been cited well over 1100 times, an attempt to replicate its findings would seem warranted…”

Figure 1: Histogram of Crossref citation counts for 2854 empirical research papers from the psychological literature. The black vertical line represents the median of the distribution. 1.7% of papers were cited more than 400 times. For visual purposes, these are not displayed.

Public/societal impact

Somewhat less common are appeals to the public or societal impact of a finding. This can refer to mentions of the finding in the popular press, bringing up altmetrics-related numbers, practical use cases of the findings such as in therapy or in court cases, or the public policy informed by a particular finding. The three examples listed below are just a sample of the justifications deployed in the literature:

Example (public impact): Connors et al. (2016)

“This research was also featured in such premiere outlets as Scientific American Mind, The Financial Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Huffington Post, NBC News and The Globe and Mail…”

Example (policy): Mcarthy et al. (2016)

“The 10 Commandments study also has political implications: It was cited as a critical building block of self-concept maintenance theory in a set of policy recommendations made to President Obama as part of the REVISE model (Shahar, Gino, Barkan, & Ariely, 2015)…”

Example: (practical implementation): Pashler, Rohrer, and Harris (2013)

“If this effect is robust, it would seem to have considerable potential impact in practical areas. Collection of self-report data from people is a commonplace and costly activity in domains ranging from marketing research to public health and opinion polling. A very low-cost method of increasing candor from respondents would have major significance…”

Methodological concerns

The umbrella term “methodological concerns” covers perhaps the largest range of qualitatively different justifications. However, they share a fundamental similarity: they all express some doubt in the conclusions of the original research.

The reason for doubt varies. In some cases, original estimates of quantities are just not very precise, and researchers may express a desire to increase the accuracy, or narrow the confidence intervals, of a given estimate. In other cases, there may be reasons to believe that the original estimates cannot be trusted due to failures to replicate conceptually similar findings, due to contradicting findings in the existing literature, or the replicating researcher may suspect that questionable research practices (QRPs) or publication bias is biasing the reported numbers. I have not seen these concerns directed towards the the original study authors personally, but replicating authors might refer to widespread problems with QRPs in general. For example, they might express suspicion based on the general tendency for effect sizes in psychology to be overestimated. Finally, replicating authors may simply point out that few or no direct replications of the original finding exist, and/or that the original authors have called for replication of their own findings. The examples listed below do not capture the full nuance of justifications based on methodological concerns. I refer the interested reader to the spreadsheet for more cases.

Example (imprecise estimate): Donnellan, Lucas, and Cesario (2015)

“We undertook this [replication] effort for at least three reasons… First and foremost, the original studies were based on small samples (n = 51 and n = 41) and therefore they generated effect size estimates with relatively wide confidence intervals…”

Example (QRPs): Harris et al. (2013)

“it seems at least possible that the social and goal priming literature might contain many large observed effects due to numerous false alarms. This could occur if a great number of small underpowered experiments have been conducted, with only those results reaching significance having been published…”

Example (lack of replications): Cheung et al. (2016)

“No direct replications of [the original] study have been published. This RRR is designed to provide a direct replication of this influential finding and to provide a more precise estimate of the size of the effect…”

Example (Existing evidence is equivocal): Sinclair, Hood, and Wright (2014)

“Since the original study, replications of the effect have been elusive… Few studies find support for anything approximating the effect. Instead, most find the ‘‘social network effect’’ whereby disapproval from one’s social network – whether family or friends – leads to declines in romantic relationship quality… A limitation of the counterevidence for the Romeo and Juliet effect is the fact that none of the follow-up studies used the original scales.”

Large Scale Collaborations

A discussion of replication justifications would not be complete without considering how the large scale lab replication collaborations like Many Labs and the Reproducibility Projects justify their sampling procedures. These are special cases in at least three ways.

- The authors are often interested in introducing some element of randomness into the study selection process in order to get a more representative sample from the population of effects in the literature.

- Because of the sheer volume of replication efforts to be undertaken, practical constraints such as the length of the experimental design become an issue.

- Because they are all preregistered, and original study selection is part of their sampling procedure, justifications are usually more elaborate than for the average replication study.

The exact justification text varies somewhat from project to project. It is however interesting to note that academic impact features in the justification process for almost all of these large scale projects. I refer the reader to the spreadsheet for details of each collaboration’s justifications.

Caveats & Summary

I do want to highlight some caveats of this project. First and foremost, I did not apply formal qualitative methods to this literature search, nor did I comprehensively comb through the literature to make sure I discovered every available justification out there. I am sure that there are more examples of justifications in studies I did not review. In fact, I am pretty sure there are justifications in the papers I did review that I might have missed. Second, as was pointed out to me by a colleague, there is no guarantee that the justifications that authors put down in their papers are the real reasons for why they choose this studyover that study. If researchers sometimes rewrite the introduction section of their original research papers to spice up the importance of their work, they might also do this when writing replication-research papers. For example, the researchers could have been motivated purely by strong personal doubts in an effect, but might choose to refer to the citations of the original work because this seems more objective. Finally, the overwhelming majority of the replication reports reviewed here are from psychological science, and scholars in other fields of science may of course have widely differing justifications for conducting replications. Consider this a non-representative sample of possible justifications. If you think I have missed important justifications, or mischaracterized the intentions of any author mentioned here, let me know!

In the paper I am working on, I hope to elaborate more on how researchers could formalize some of these justifications by specifying formulas for replication value. Until then, I hope this will serve as a useful starting point if you are looking to do replication research, and are curious about how researchers go about justifying which finding to replicate.

Happy replicating!

Updates

- A registered and citeable version of this blog post, including a copy of the linked spreadsheet, is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1286715

Spreadsheet of Justifications

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1HzBePXvDAeGu8ND04E18u7BynT75LgW4vcLFNDUn7GU/edit?usp=sharing

The spreadsheet include quotes from the 85 papers reviewed for this piece. Please note the following:

- Three dots (…) signal that text has been skipped.

- Square brackets [] signal paraphrasing.

- Cells in the “DOI” column are listed as NA when a DOI could not be obtained.

- Cells “Replication Justifications” column are listed as NA when no discernable justification for the replication could be derived from either the introduction or discussion section of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Nicholas Coles, Christopher Harms, Daniël Lakens, and Leonid Tiokhin for helpful comments and suggestions on drafts for this post. Thanks to Etienne LeBel for curating the dataset used for this post and making it freely available online. Thanks to Sanjay Srivastava for making me aware of some recent replications not included in the CurateScience dataset.